To do any important thing, we have to set aside and ignore other important things.

And there are always other important things.

To do any important thing, we have to set aside and ignore other important things.

And there are always other important things.

When you’re a new member in a group or organization, it can feel uncomfortable — particularly if everyone else knows how the system works and they know what to do.

It’s not incompetence; it’s uncertainty. Not a lack of ability, but a question of what to do and when.

This can happen in a larger context, too. It’s easy to tell ourselves the story that everyone else knows what they’re doing. That everyone else knows the system and that we’re an outsider.

But again — real or imagined — this has less to do with ability and more to do with learning how a particular game is played.

When this kind of discomfort arises, remembering to trust yourself is a good first step.

Well-worn grooves are just that: well-worn. They’re comfortable and familiar.

So sometimes what we need is a bit of jostling. Electively or unexpectedly, an unsettling of the repetition.

Because we’re not machines. And anyway, we have machines to do machine work.

What we need is the right balance of pattern and surprise, of known and new.

And for that to happen, we have to find ways to exit the grooves.

“Are you ready to order?” The server stood next to our table attentively, hands behind his back.

He listened carefully as each of us let him know what we wanted to eat.

I marveled. My own short-term memory would be woefully inadequate for this sort of thing. Relaying to the kitchen a food order for a family of five — without taking notes? Not my skill-set.

But here he was, no pad, no pencil, no tablet.

And when our meal was served, only one of the meals was completely accurate.

Turns out, this server’s short-term memory wasn’t all that great either.

My son quietly noted, “Maybe he should have used a pencil and paper.”

Indeed.

Style over accuracy. It looked impressive — but that’s about all.

Sometimes we need to humbly choose practical methods; they might not garner oohs and ahs, but they’ll get the job done right.

Even the greatest professional athletes have errant shots.

And the best orators misspeak.

And the most skilled doctors err.

There is no “so good that that errors are impossible.”

So remind yourself.

When a recipe flops. Or a blog post doesn’t land. Or a photo shoot feel stale. Or a composition fizzles.

This is natural. And it happens to the best of the best.

Peak performance can never be a permanent state. But neither can falling short.

It’s all part of the practice.

We can bristle when we hear someone tell us what we should do.

(I’m an independent thinker. Don’t tell me what to do, thank you very much.)

But selective enrollment in the “shoulds” others suggest to us can be transformational.

And indeed — sometimes — when we choose to adopt the (even off-hand) suggestions of others, it’s to great and wonderful effect.

Take any two points in a creative life, and it’s anyone’s guess whether things move in the direction of better or worse. And the amplitude can be astonishing; high highs and low lows.

But over time, a creative practice is generous; it correlates in a positive direction.

* * *

Beware of giving too much attention to any one segment. Instead, step back and appreciate the long dance … and the beauty of its inflection points.

Bruce Lee famously said, “Be water, my friend.” Here’s a slightly longer version of what he said, because it’s worth pondering:

“Empty your mind. Be formless. Shapeless. Like water.

“Now, you put water into a cup — it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot … it becomes the teapot.

“Now, water can flow, or it can crash.

“Be water, my friend.”

You have a routine: things you do most days, like clockwork.

And others have routines too.

Which means in some instances, you’re a part of someone else’s routine.

And they’d miss you if you were gone.

Whether it’s a face-to-face encounter, or through the work you put into the world — our routines can intersect with occasional regularity.

Appreciate the subtlety and beauty of the overlaps.

During a road trip, I noticed that we had 3 hours and 15 minutes until our next stop. In my head, I thought, “OK. We’ve got about three hours left.”

Half an hour later, my son saw that we had 2 hours and 45 minutes remaining. He groaned, “Ugh. We still have three hours left.”

It was a strange phenomenon for me. As though we had made zero progress for half an hour.

So use caution when rounding. Do it too often, and it might feel like you’re not getting anywhere.

In front of where we were sitting, there was a 30-gallon garbage bag full of trash. We were at a little league field, and the bag was left by a previous group. There it sat, leaning against the outfield fence.

Option one: be annoyed by the lack of courtesy. Lament the irresponsibility. Spend the game as spectators of sport, and spectators of trash.

Option two: carry the bag to a dumpster. Wash hands. Move on. Enjoy the view. Enjoy the game.

(I went with option two.)

Sometimes we have a choice: point to the problem and live with it; or solve the problem and live free of it.

The latter is often more satisfying.

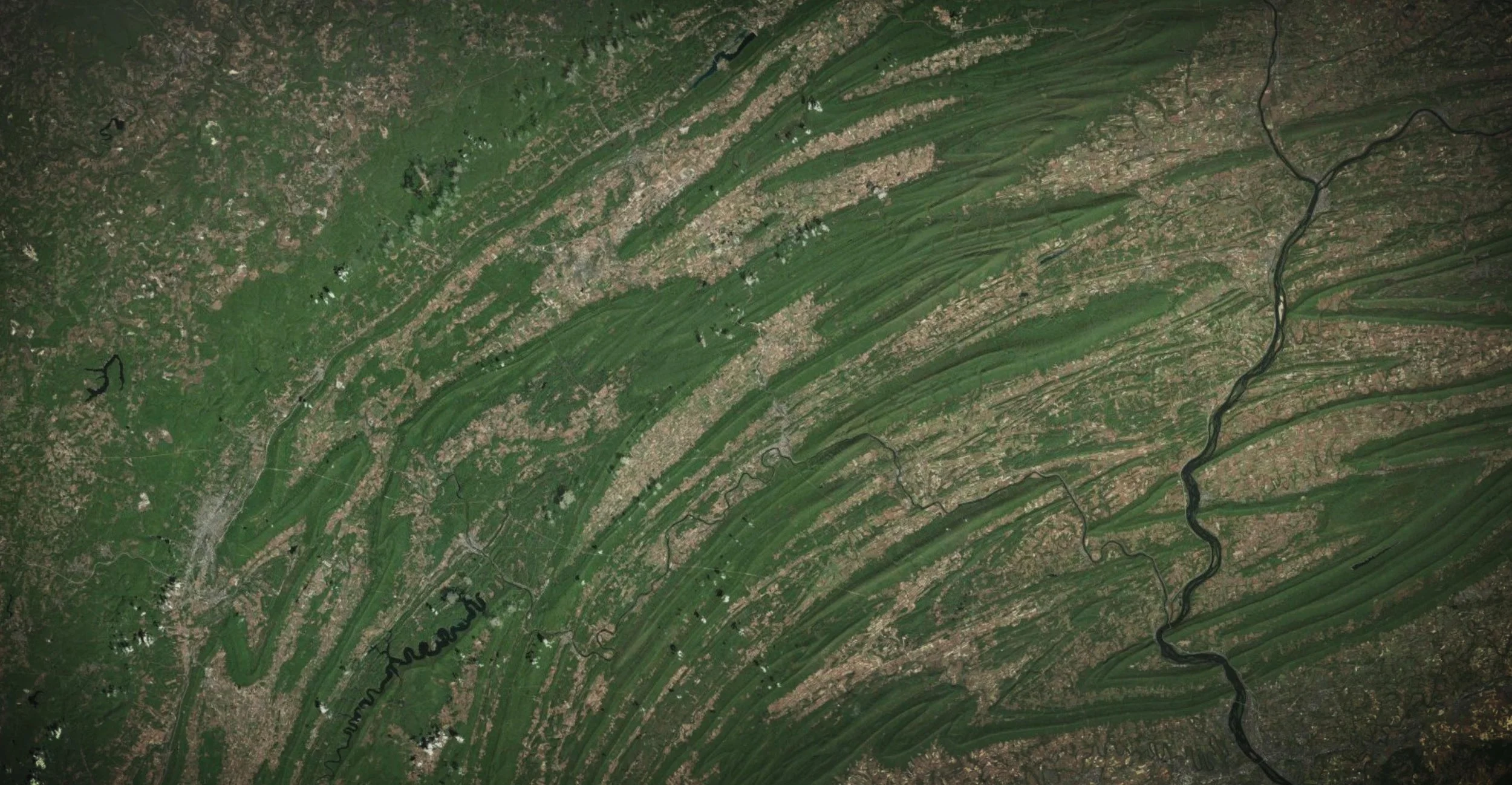

If you’ve visited this blog at savenwood.com, you may have noticed the header image on the site: a swirling pattern of greens and browns. An aerial image. But of what?

This is the geographic origin of the blog you’re reading. More specifically, the location of its author.

From Google Earth, it’s an image of where I am on the east side of North America, from the perspective of about 100 miles above sea level.

* * *

Sometimes to locate ourselves, we need to zoom out. Way out. And we can simultaneously note our very small place, as well as the remarkable reach of our connections across the planet.

Here’s to living on the ground and seeing from the clouds.

Every so often, you may feel an unexpected boost of optimism. An unwarranted, unexplained sense of possibility.

In these moments, the rational brain may caution pause. There are reasons to be pessimistic. Exercise restraint.

But we can mute the rational brain — temporarily.

Lean into possibility when the feeling arises; it’s a gift. Don’t grip it tightly, but hold its hand. Even if only for a little while.

Colleague: “We don’t have a good system to do this.”

Me: “OK. Then let’s use a bad system.”

* * *

Because we don’t always have the right tools. Or rather, we don’t always have optimal tools.

And when a task is necessary, sometimes we need to go with good-enough tools.

It’s easy to convince ourselves that sub-optimal is untenable. But often, what’s untenable is inaction for want of what’s optimal.

An engineer was explaining his project to some colleagues. In showing an incomplete feature, he prefaced it with, “Try to imagine with me …”

What a beautiful prompt. What an excellent invitation to a specific posture. A memorable line worth using more often.

When you’re compelled to run from home — away from what’s precious to you — there comes a time when you’re furthest away, spirit waning. And all it takes is turning back toward center for new energy to take hold.

When home is the destination, our resolve is bright.

This seems like a metaphor — and indeed it is — but it’s also something I often experience when I go for a run. There’s something about knowing you’re on your way back home that keeps the legs moving.

In the 2024 Winter Youth Olympics, Yang Jingru of Team China chose an unusual strategy in the women's short track speed skating 1500m final.

While many racers pace themselves so they can sprint at the end, Yang Jingru chose a different method. Soon after the race got underway, halfway through the first lap, she darted out to the lead in a full sprint. She kept going until she nearly lapped the rest of the racers.

By the time the main group had finished their third lap, Yang Jingru was coasting comfortably at the back of the pack … but finishing her own fourth lap.

Unsurprisingly, she went on to win the gold medal.

* * *

Keep your focus. Race at your own pace. But remember: sometimes the person behind you has already finished the race you’re trying to win.

You can see the race here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qgl1GITk0Js

You may be the undeserving recipient of someone else’s disappointment. And it might be totally unrelated to you … except that you’re the recipient.

Likewise, you may be the undeserving recipient of someone else’s joy.

This is the way things work; lots of feelings are misplaced in the world.

When you can, be someone who spreads joy more than disappointment. It’s a virtuous cycle worthy of your contribution.

Sometimes, practice makes perfect. But more predictably, practice makes permanent.

Which brings more attention to the question: what are you practicing? And how are you practicing it?

Because over time, the way you’ve been practicing becomes harder and harder to change.

In sports, the sweet spot of a bat, racket, or clubface is the small area that yields the best results. When you hit a ball with the sweet spot, there’s little vibration and maximum trajectory.

And notably, it’s a spot. Not a zone. Not an area. But a small spot.

Too far one way or another, and the results are suboptimal.

In life, we’re often seeking the sweet spot. In the various things we balance, in the connections we seek, in the ways we engage. And that careful calibration can feel burdensome.

But the thing about the sweet spot — when we find it — is that it feels effortless. Once we’re able to locate the sweet spot, our inputs feel easy and the outputs are remarkable.

Keep at it. Keep searching. Find it.